Photo Essay: Helping a Mali Village Confront a Water Crisis

by Alex Mavrocordatos

Theatre for development is a particularly effective form of communication for social change. Alex Mavrocordatos worked on, and photographed, a successful example of theatre for development that, over five months' time, fostered social change in Kolo, a small Mali village. Theatre for development is a dialogic type of theatre, ensuring everyone is engaged in mutual listening, learning and communication. Dialogue occurs between performers and their peer audience as well as between performers and a nongovernmental organization or field worker audience. Mavrocordatos is a founding member of The Centre for the Arts in Development Communications (www.cdcarts.org), from whose archive this photo essay is drawn.

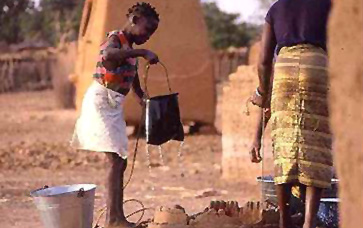

It was the dry season in Kolo, Mali. To make matters worse, drought had withered crops and almost completely dried up Kolo's nearest river, the Bani. Shallow wells in the village also ran dry. Villagers dug new wells, but in the sandy soil, these wells collapsed.

The entire village had to rely on a single communal pump, shared with a nearby hamlet and situated some hundred yards from Kolo.

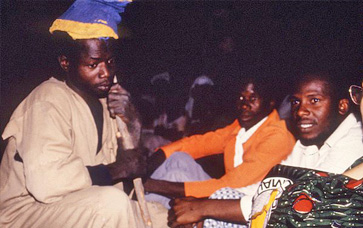

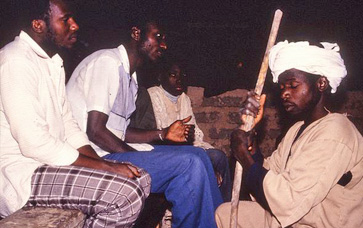

March 1988: After dark, Kolo villagers, including the chief and village elders, gathered to watch a youth group give its weekly performance of kote-ba theatre.

Kote-ba is an improvised form of theatrical expression in Mali that lends itself well to theatre for development. Through the spontaneity of improvisation the actors are able to draw audience members into their play"and when those particular spectators are field workers from World Neighbours and Oxfam, the drama lends an extra poignancy and efficacy to the sentiments expressed by the young actors. World Neighbours is a global nongovernmental organization that runs local self-empowerment projects in the area. Two field workers from the NGO were in the audience watching the performance.

That night, the performers, who, because of their age are not permitted to express opinions during village meetings, planned to use theatre for development to address Kolo's water crisis.

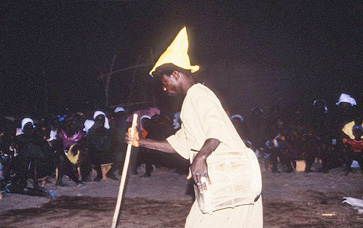

The actors dressed like the village elders. One, a talented mimic, wore a smock identical to that worn by the village chief, and he carried a similar stick.

The performance depicted an old man and his family whose own well has collapsed. The old man complained to the "chief." The actor symbolically depicted the dried out well.

The actor chief summoned his "elders." Together they decided to ask World Neighbours to donate a tube well.

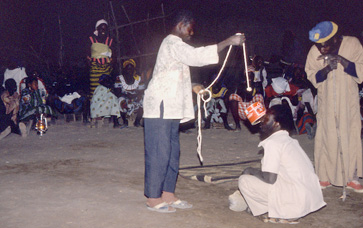

So, the actor chief left the performance area and went into the audience, directly to the World Neighbours field workers, who suddenly changed from spectators to being actors in the play.

The actor chief"with only the authority vested in him by virtue of theatre, held a real meeting, negotiating directly with the representatives of World Neighbours. A theatrical event suddenly went beyond merely pointing to possible change: It became, itself, a seminal moment of change. And the entire village was there to see it.

The field-workers explained that they couldn't donate a tube well. Instead, they promised that if the villagers rebuilt wells closer to the Bani River, World Neighbours would provide technical and material support. The "chief" took this message back to his "elders."

The performance ended amid cheers and laughter. Also, the "real" elders openly demonstrated their appreciation.

During the following weeks, the villagers held meetings and drew up plans. Every kote-ba performance included a sequel to the water play, becoming a kind of soap opera, following the same family's progress towards the digging of a community well.

The final performance included an exhortation to all able-bodied people to turn out and dig the well.