Photo Essay: How Does Communication for Social Change Impact the Lives of Women Refugees

by Lourdes Margarita Caballero

This Spring, Lourdes Margarita Caballero, a communication associate at the Consortium, travelled to the Kiziba Refugee Camp, in Karongi District of western Rwanda for a first-hand look at the camp’s Abakundanye association. Her goal was to learn how communication for social change has impacted positively on the lives of the female Congolese refugees in this cooperative. She found that communication fostered collective responsibility and helped the women feel less lonely and more powerful.

Introduction

One of the big questions on my mind during my first trip to the Kiziba refugee camp in Karongi district, western Rwanda, was how communication for social change created a sense of collective responsibility among Congolese women from the Abakundanye association. In Kinyarwanda, Rwanda’s indigenous national language, “Abakundanye” means “Those who love one another.” I also wanted to learn how CFSC has become a pathway for the women in the association to become empowered in a place where they faced dehumanisation daily.

More than 10,000 of the 18,000 refugees at the Kiziba refugee camp are women. They fled the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) because of persistent violent conflicts that plague the Great Lakes Region. The trauma of displacement combined with social isolation and the humiliation of poverty, burdens both young and old women in the camps. They also endure the scourge of sexual- and gender-based violence. “People who are young get taken advantage of, and HIV goes to your body. Fifteen, 17, and 18 year old women can get prostituted,” said one woman at the camp.

As long as peace and security in the DRC remain elusive, there is little hope that the 55,000 plus refugees based in three camps, Kiziba, Gihembe and Nyabiheke, and two transit centres, Nkamira and Nyagatare, can go home. It is important for communicators to listen to the women's perspective in order to understand the crisis and help them transform their reality. Brazilian educator Paulo Freire wrote that it is through people's active reflection on their reality that they begin to understand their oppression and improve their ability to remake it. Nowhere was such a transformation more needed than in isolated refugee camps where women struggle daily to maintain their dignity.

The Birth of the Abakundanye Association

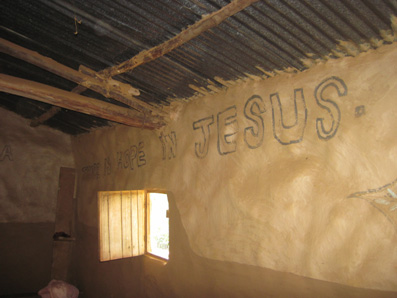

On a March afternoon, fifteen women at the Kiziba refugee camp gathered to talk about their stories. We were inside a mud-built chapel with no lights save for the afternoon sun streaming through a few wooden windows.

The camp's chapel has the words “THERE IS HOPE IN JESUS”

scrawled on the mud walls at the back for decoration and inspiration.

The session started with rousing praise and worship music. Using no instruments, they began clapping, stamping their feet and swaying to the rhythm. Their strong voices filled the emptiness of the chapel.

The women from Abakundanye association represent different churches.

Here they are singing songs of praise at the start of a session with

the author. The Congolese women are able to speak the local language,

Kinyarwanda, because they have been in the camps for many years.

They often invoke God in their stories.

Three women, Mugiraneza Jolie, Mathilde* and Innocent*, introduced us to the rigours of camp life (*not their real names).

Mathilde, a widow from Gatanga, Lubumbashi, DRC, lost her

husband in the war nine years ago. She has six children

to feed, and there is never enough food at the refugee camp.

As she rocked her youngest child, Mathilde said:

In 2001, I came here with five kids. Someone gave me 5000 RWF (US$9), and I got pregnant. I wanted to buy clothes, and I got a baby. I used to have a garden and a good family and I used to do small business selling fish. There are people who have been here for 10 years, six years, five years. We don't even know the end of our stay here. Because of our problems we put ourselves together in an association.

Mugiraneza Jolie, one of the founders of the Abakundanye

association, is also a councillor for the association.

Mugiraneza Jolie said she and 28 other women set up the Abakundanye association in 2006 to help each other become more self-reliant. She said:

If we meet together and if we have one heart, the association can help you and support you and can help you heal your broken heartedness. You teach each other and you teach your friends, and if you have problems, you pray together.

Jolie and two other women had attended an intensive training session for women leaders held in the nearby town of Kibuye. A faith-based organisation, Peace Building, Healing and Reconciliation Program (PHARP) structured the session.

PHARP is an international NGO operating in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and Sudan. Its strategy, according to its Web site, is to “maximize programmes’ impact through interventions designed to build local capacity through participatory approaches, strengthening the community sense of ownership of the projects and promoting project sustainability.”

Indeed, it was Julienne Mukansanga, coordinator of PHARP’s Women and Children's Program who had brought me to the chapel that afternoon to learn about the women’s struggles and how they were trying to help themselves. I observed the women spoke candidly about their experiences to her and openly answered her questions. I saw it as a sign of how organisations like PHARP have built strong relationships with women from the grassroots. Indeed, organisations like PHARP thrive in Rwanda because they provide financial, spiritual and moral support to communities—especially those afflicted with HIV.

“PHARP invited people from different churches to help each other from isolation,” said Jolie. “They taught us how to forgive those who have hurt us so that we can live in peace.” In addition to Bible studies and sewing classes, the women who attended learned how to organise themselves. When she returned to Kiziba, Jolie shared what she had learned about organisation with other women. She said:

We started a small group and some of them were ready to respond to our invitation. And I said to them, 'Please think about what I am telling you and we can help each other. There's no other way. We can work together, share, and see what we can do so that we can help each other. That's how we can manage.’

In the last four years, the association increased its membership with women from different churches—Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh Day Adventist, etc. When their two sewing machines were working, the women met every afternoon to teach each other to sew and how to organise. They discussed ways to be more financially independent. They shared health and nutrition information. And they learned ways to help other women recover from broken hearts.

Outside the mud chapel, Lourdes Caballero poses with 16 women from the

Abakundanye Association and Julienne Mukansanga, representing

the Peacebuilding, Healing and Reconciliation Program-Rwanda.

The Value of Communication and Participation

Innocent is another member of the Abakundanye Association.

She said

that

camp life was hard without the association.

“Those who are isolated are the ones who have many problems.”

According to Innocent, another association member, active participation slowly built solidarity among the members. “The life here is hard when you are not part of the association,” she said, adding that Abakundanye rescued women from feeling helpless by engaging them in mutual support groups. “Those who are trying to have something to do … , feel better and they can go to work. By being in an association, you can help each other.”

Meeting regularly created new social ties and helped the women rebuild their fractured communities. This helped to overcome the hopelessness many refugees in Rwanda suffer because of their prolonged displacement. Mugiraneza Jolie explained:

We can be isolated, each and every one. If we are isolated, we cannot know each other's problems … . and many are sad. They just go in their small house and cry, and we found that it's not helpful. [We said,] ‘Let's be together and share our problems so that we can help each other and move from one place to another place.’ Many of us are happy, very happy.

Association members helped each other gain income-generating skills through sewing. By sewing school uniforms, the women didn’t have to beg their husbands for money. They were able to buy themselves new shoes.

Abakundanye also functions as a cooperative. It gives women small start-up money for their projects. Each member contributes 5000 RWF (US$9) to a common fund, and at the end of each cycle, the sum is awarded to a borrower. From her earnings, the borrower returns 500 RWF (US$0.9) to the association. The association has given money to six women so far.

The women’s network augments one another's limited food rations when possible. Malnutrition is common and the rate of stunted growth in Kiziba was the highest in Rwanda's refugee camps. Because women are traditionally charged with providing food for the family, poverty increased the pressure to find alternate ways to obtain food or to trade it for non-food items. Mathilde said:

We used to eat three times in a day and now only once. Sometimes we do not even get that one ... . We always have to wait for the camp to bring us food... . We got food like 10 kilos of maize. That means you have to make it into flour from the maize and you can finish it in the house. As we have the association, your friend can give you three kilos. And you can help buy shoes for the children.

During afternoon meetings at the association, the women exchange advice on how to keep their families healthy. Topics include nutritional topics such as how to cook tomatoes, peanuts, sauce and fish. Ensuring healthy food for refugees is a critical issue to the association. Many children eat only once a day, which increases the likelihood of malnutrition and disease.

Mathilde said that relying on camp food alone is not advisable:

When you have a small child and you give the food for adults, you can have child malnutrition. You can add fruit, avocado, banana, small fish and it can help the children. If we just depend on the food at the camps, your child will get malnutrition.

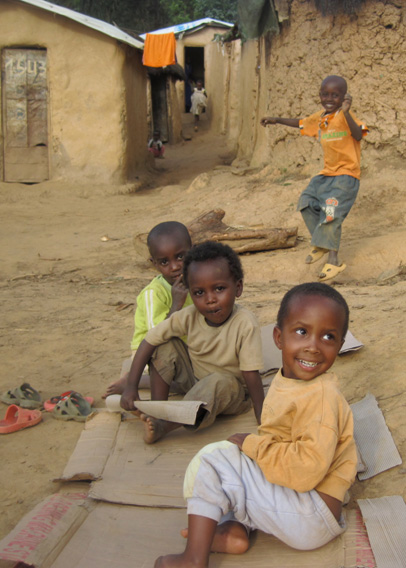

Association members work to provide a better life for their children.

Here, young children use discarded boxes as mats, since roads are

not paved in the refugee camp and are very dusty.

At their daily meetings, association members encourage each other to subscribe to family planning to provide a better future for their children. Mugiraneza said, “We meet and share [information] about family planning and … [how] to be able to take care of [our children’s] education.”

Congolese children visit Lourdes Caballero. One boy makes others laugh by

trying to

balance a huge can of vegetable-fortified food from the United States

on her head. Ensuring healthy food for refugees is a critical issue to the

Association. Many children eat only once a day, which increases the likelihood

of malnutrition and disease.

Communication as a Pathway to Personal Transformation

What is clear from the experience of the Abakundanye, is that vulnerable women use communication to assert their presence in the community. Although isolated, illiterate, and extremely poor, they refused to be invisible. And while acknowledging their poverty, the women believe they have much to give. “We don't have any money to buy soda for you or something,” said Mathilde, “but we have many things to share.”

Their testimonies demand respect for their role in ensuring the well-being of their community. Simply pouring in humanitarian aid cannot sustain the camps. The women in the camps understand better what works and what doesn't. They must be more engaged in decision-making about issues affecting their lives..

Storytelling and dialogue are important for them in their resistance to being classified as statistics. Both are essential elements in the CFSC that includes reflection and action by the women. In her 1986 article “Communication as if People Matter,” Mina Ramirez suggested creating a social climate for storytelling as a form of alternative communication meant to make the powerful listen. She wrote, “A people who have been utterly disregarded in the interests of material accumulation by national global powers should be given the chance to articulate and express their deepest human feelings about the realities of their life.”

The women of Abakundanye are strengthening their capacity to communicate and learning how to participate. The organisation is still very young, so the women need support that will enable members to explore the many ways they can get involved in spite of their limited means. Doing so means negating the stereotype that refugees only wait helplessly for aid.

The association women knew they needed to work together as a unit, be creative and vigilant in order to combat pervasive hopelessness. Their desire to transform their situation explains why so much of their conversations focus on motivating each other. But transformation is not possible without a critical understanding of their situation.

During my visit, I saw this transformation unfold when the women discussed their thoughts about humanitarian aid. They recognised that, although they rely on donations to survive, donations are not enough to make them feel truly alive. Mathilde explained, “We depend on donations. Some people came to visit us and they gave us 1000 RWF. We depend on that until the bad days go. The food that we got as donation is just helping with the hut but not food we can depend on for life.” The impetus for action was born out of the common belief that, to resist dependency and gain control, they had to work together.

They were also aware that they need collaborators to help them become more independent. When members are hungry and sick, or the association can not get needed financial or technical support, its operations are severely impacted.

For example, when one of their sewing machines broke, the women did not have the funds to repair it. They tried to raise the money to bring the machine to the capital, Kigali, 3.5 hours away, for repair, but after a year and a half, they had only been able to save 9,000 RWF (US$16) of the estimated 20,000 RWF (US$35) needed. Jolie and other association leaders rallied to keep the group together, but without the sewing machine, their daily meetings dwindled to weekly encounters.

A repairman from the capital sets up replacement sewing machine for the association.

Through the support of PHARP-Rwanda, the women were able to work out an agreement for the machine's repair. They received a replacement machine, which energised the women and the association.

Association members begin using their new sewing machine.

Constraints and Opportunities in Strengthening Grassroots Communication

Many times, the value of communication and participation of marginalised women has been underestimated or ignored in contexts of conflict or crises.[1],[2] The stories the women of the Abukandanye association told show that, when nurtured, communication and participation are as lifesaving as relief goods. They have the potential to restore human dignity and inspire reflection and action.

Women's meaningful participation is one of the Five Commitments of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). But gaps exist in consistent implementation. For instance, 2008 data from 110 refugee camps reveals that women's participation in refugee camp committees stood at merely 39 per cent.[3] This was alarming because the figure was even smaller compared to data for the period between 2005 and 2007.

Women's meaningful participation receives much less than other programs in budgets. The annual budget of UNHCR for community participation in refugee camps for 2010 in Rwanda, for example, received the third-lowest budget among eight programs.[4] Funding for security from violence and exploitation, including gender-based violence was even lower.

It’s important to challenge communicators to hold relief agencies accountable to their promises. It is also important to investigate how vocational, health, community mobilisation programs conducted by UNHCR and its implementing partners have enabled women and men to become more engaged. Life in refugee camps has disrupted relationships and traditional gender roles. Some men feel that women are “married” to aid groups because they provide everything, diminishing the men's role.

The women of Abakundanye know they cannot make all the necessary changes alone. Mugiraneza Jolie said to us, “Please think of us and be close to us and help us where we can work from.” These women need allies who will treat them as partners as they learn to gain control over their future. For this to happen, traditional decision-makers must listen to their voices.

The author thanks Julienne Mukansanga of PHARP Rwanda who facilitated the meeting, the translator Baraka Paulette and the women of Abakundanye association.

References

UNHCR (2001). Respect our rights: Report on the dialogue with refugee women. Retrieved from: Author http://www.unhcr.org/3bb44d908.html [accessed 28 April 2010]

Young, W. (2002). NGO statement on refugee women. Retrieved from: International Council of Voluntary Agencies http://www.icva.ch/doc00000864.html [accessed 29 April 2010]

Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Program (2009). Report on international protection of women and girls in displacement. Retrieved from: UNHCR www.unhcr.org/refworld/pdfid/4a5c594e1c.pdf [accessed 29 April 2010]

UNHCR (2010). UNHCR Global appeal 2010-2011. Retrieved from: Author http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e45c576 [accessed 30 April 2010]

[1] UNHCR (2001). Respect our rights: Report on the dialogue with refugee women. Retrieved from: Author http://www.unhcr.org/3bb44d908.html [accessed 28 April 2010]

[2] Young, W. (2002). NGO statement on refugee women. Retrieved from: International Council of Voluntary Agencies http://www.icva.ch/doc00000864.html [accessed 29 April 2010]

[3] Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Program (2009). Report on international protection of women and girls in displacement. Retrieved from: UNHCR www.unhcr.org/refworld/pdfid/4a5c594e1c.pdf [accessed 29 April 2010]

[4] UNHCR (2010). UNHCR Global appeal 2010-2011. Retrieved from: Author http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e45c576 [accessed 30 April 2010]