Photo Essay: Using Communication to Help Bring Education for All in Lesotho

Photos and text by Joanne Edgar with support from Laurence Mach

The Kingdom of Lesotho is a small mountainous country completely surrounded by South Africa. It is a peaceful, politically stable country; a nation with a traditionally high literacy rate when compared with other African countries. The people of Lesotho place a high value on education which they view as a human right for all citizens. Lesotho’s constitution encourages fundamental education for all.

Yet attaining total access to education remains a struggle fueled by economic and social challenges. Unemployment exceeds 50 percent, for example. HIV/AIDS prevalence in Lesotho is the third highest in the world (as a percentage of population), estimated at more than 27 percent of sexually active people. The number of orphans, resulting from the AIDS crisis, is nearly 10 percent of the total population.

Despite this, Lesotho’s Ministry of Education and Training developed an Education Sector Strategic Plan outlining ambitious goals for the country to achieve “education for all” by the year 2015.

To support the initiative, the Communication for Social Change Consortium developed a communication plan that addresses elements of Lesotho’s Education Sector Strategic Plan and applies Consortium’s thinking about how community dialogue can bring about Education for All in the next seven to 10 years.

This proposed Education for All communication approach will help accomplish two key goals:

- To reach and enroll in school the 15 percent of Lesotho children not currently enrolled, and

- To build a national consensus in support of basic education, i.e., at least 10 consecutive years of education for each citizen of Lesotho.

Both goals are quantifiable, measurable and do-able, and each is achievable with the help of a communication approach that’s inclusive, open and that fosters an environment in which people who are poor and without power tell their stories, define their goals and work together to achieve those goals.

An important component of the Consortium’s communication plan is encouraging people throughout Lesotho to voice their opinions and tell their stories in their own ways about living conditions in their country. This view from the Maseru airport gives a sense of the terrain which also exacerbates the harsh economic conditions.

Denise Gray-Felder, Consortium president, accompanied by Joanne Edgar, traveled recently in Lesotho to hear what the Basotho people think about education for all.

Gray-Felder and Edgar presented the Consortium’s communication approach to 300 principals and educators at meetings in Maseru, Lesotho’s capital. They listened to educators’ stories about improving education throughout the nation. Many of the schools in the country are run by churches.

Bernard Batidzirai, UNICEF education officer, Lesotho, manages the UN’s education portfolio in this country.

Thuto Ntsekhe-Mokhehle (left), Lesotho Ministry of Education and Training, and Lati Makera Letsela, UNICEF, are key partners in the education for all initiative.

Lesotho educators are optimistic and determined to improve their schools and achieve Education for All.

Gray-Felder and Edgar also visited three Lesotho schools to view first hand the challenges bringing Education to All. On the way to visit a school in the highlands, they passed herd boys with their cattle. Herd boys make up a large percentage of those children not enrolled in school.

The communication plan aims to assist Lesotho’s effort to enroll all children, including this herd boy, in school.

In the highlands village of Makoetje, 400 children, ages six to 16, attend this primary school. Primary school education is free for all Basotho children.

There is no heat or hot water. Windows are broken. Most students sit on the floor.

This outdoor latrine is used by all the children in the school, boys and girls.

The school’s principal leaves her home and family behind in Maseru (the lowlands) every weekend to travel nearly two hours by car up a steep mountain pass to live in, and teach the children of the village.

After completing seven forms (grades), children have the option to go on to secondary school, which is farther away and charges fees for an additional three forms.

Many families cannot afford the secondary school fees. For example, this 17-year old girl, an orphan living with her elderly grandmother, is repeating the seventh form because she doesn’t have money to pay the secondary-school fees, but she doesn’t want to stop going to school.

Gray-Felder listens to the stories of some of the school’s children.

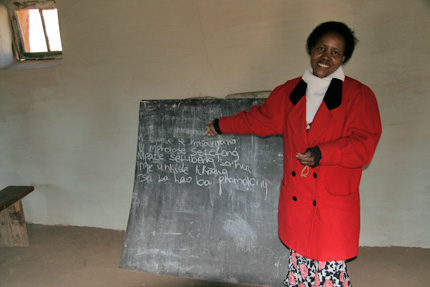

She talks with a woman elder – the former principal of the village school and the best educated woman from that village, learning about her experiences as a teacher.

At the Thamae Primary School in Maseru, teenaged students sing frequently as a form of entertainment and to welcome visitors.

Facilities in this school differ vastly from that of the mountain village.

Bibo Hoohlo is a primary school in Maseru.

Here, too, the students have a different school experience from the students in the mountain village

These Maseru high school students are members of the Girls and Boys Education Movement (founded by Unicef Lesotho) and trained as peer counselors; youth leaders who encourage others to complete their schooling. They travel the country advocating for education and healthy lifestyles among youth.