How Ethiopian Youth and Community Dialogues Fight HIV/AIDS by Ailish Byrne

Photos by Ailish Byrne.

"Our club is special. We are AIDS orphans. If we teach people about AIDS, society will accept without any problem. We can make a big difference."

"People who are 40 years old and 50 years old run other youth centres. How can they raise issues of young people? They are old people. If they 'represent' us, and we are not seen as responsible for our situation, who will know?"

People often ask why dialogue is important, what it achieves and why we should support such activities. Being core to the Consortium's values and mission, our support for dialogue processes across the world takes different forms.

Since 2004 we have been actively involved in Ethiopia, working closely with UNICEF and the government HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office (HAPCO) in particular, to strengthen communication for social change initiatives and develop capacity to monitor and evaluate them in participatory ways. This innovative work, at scale, creates exciting opportunities to enhance the impact of HIV/AIDS initiatives across Ethiopia.

And it contributes to valuable learning of wider relevance.

This past May, my visit to Ethiopia provided the opportunity to observe dialogues in depth and discuss with key players their progress to date, the main challenges they face and future plans.

This article presents a snapshot of two dialogues to highlight what they are contributing to the lives of the people who are participants and their communities and why they feel dialogue is worth committing to. As always, the strength and potential of local people bears witness to what can be achieved, even in such otherwise resource-poor contexts.

The dialogues take place in and near Awassa, the "capital" of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People's Region of Ethiopia, with a population of approximately 15 million people, 91.4 percent of whom live in rural areas. Well known for its extreme poverty, rural isolation, diverse ethnic groups (more than 45 of them), languages and widespread harmful traditional practices (HTPs), the region is the focus of numerous development initiatives, governmental and nongovernmental.

Awassa is a four hour drive south of Addis Ababa. The journey illustrates why this is a high risk area for HIV/AIDS. Villages, people and livestock dot the main road. Women carrying large heavy yellow water buckets or queuing at wells and boreholes, and men carrying water on rickety donkey carts, are common sights. Children in faded clothes walk along the dusty road and play in brown streams, next to people washing clothes.

All along the way, we see rustic, poor, cobbled-together homes and yards, including some brightly coloured "terraces" of homes adorned with beautiful local paintings.

This major highway includes several bustling crossroads, with customs checkpoints for lorries coming and going between Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia. It is a major transit area, a place where drivers of heavy trucks billowing exhaust fumes stop often.

Why Is UNICEF Supporting Youth And Community Dialogues?

Community dialogue is a key element of UNICEF's strategy to support decentralisation and good governance in Ethiopia. To date, there has been notable success in establishing community dialogue, especially in key areas of HIV/AIDS, girls' education and harmful traditional practices. The latter are very evident in Ethiopia and include female genital cutting, early marriage, abduction, wife inheritance and extracting milk teeth (believed to cure some illnesses).

Regular dialogues provide space for people to consider such issues within their wider social and cultural contexts and dynamics, to identify and prioritise their problems, articulate their capacity and strengths, and mobilize resources for collective gain. Importantly, they are grounded in, and reaffirming of, local culture, language, knowledge and life experience. The dialogues take place every two weeks and create a regular space to explore crucial, sensitive issues in a respectful, safe environment.

The ultimate objectives of UNICEF's programme are to use communication to accelerate local ownership, shared leadership and sustained impact. UNICEF-trained facilitators now work in eight regions, focusing on HIV/AIDS within its broader "life context" of issues of poverty, unemployment, street children, gender discrimination and so on. Fundamental communication for social change and human rights principles of self-determination, participation and inclusion underlie the initiative.

This approach implies the use and advocacy of participatory approaches and methods that put into practice the key communication for social change concepts of voice (for the marginalized and excluded), space (places, media and policies that form facilitating environments) and connectivity (alliances, both horizontal and vertical). This approach also is reflected in the training and support of dialogue facilitators.

Over time, and through experience, UNICEF has developed a participatory training process and guidance material for facilitators. At all levels participants actively draw on, reflect and learn from their experience, critically examining habits and social norms in the process. Experienced regional teams train new facilitators, organize refresher training and support facilitators to document their experience. The initiatives illustrate how powerful it can be to bring groups of people together to discuss and act on their issues.

Dialogues in Action

I. Urban Youth Dialogue in Awassa Town

The dialogue took place in relatively green and peaceful garden office setting shared by several NGOs, accompanied by sounds of roosters crowing, chickens scratching and carpenters hammering.

Tsegaye Petros, HAPCO, meets local youth facilitators

just before the Awassa dialogue begins.

This dialogue involved 12 men and 11 women, several of whom were also engaged in the traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony, a regular feature.

Dialogue participants enjoy traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony.

Two UNICEF-trained youth facilitators ran the two-hour session. The focus was what they are doing as an anti-AIDS club to help control and mitigate HIV/AIDS and the challenges youth face.

UNICEF-trained youth facilitate the two-hour session.

Photo by Afework Ayele.

An anti-AIDS club (AAC) was defined by a participant as an:

""¦ informal organised college. In this and other clubs there are potential young people who can make a difference in HIV/AIDS prevention and care. AACs work to change society, especially to correct misinformation and raise awareness for attitudinal change. This is helping to create such attitudinal change so there is lots of potential."

Sign indicating where local anti-AIDS association holds meetings.

I witnessed the strength of such support groups in providing a safe space for discussion and sharing amongst the youth. This space builds confidence and fuels deeper understanding and support that they feel would not be there otherwise.

The dialogue was effectively co-facilitated, with participants engaged and eager to speak. It appeared to be a well-established group of young people familiar to, and trusting of, each other.

Participants shared their feelings in a safe space.

The quotes below show what some of the participants consider the main value and achievements of their dialogues:

A. Respected as a local initiative that contributes to better-informed communities:

"Even a child can know about HIV/AIDS. If you ask them "Who told you about HIV/AIDS?' they say "The [AA] club members.' So we are the first to disseminate information."

"There are misconceptions on teaching aids, especially posters. Drawings seen on posters are frustrating. People consider them as wild and frustrating. Now this is changing, people are coming to us instead.

"In addition to safeguarding ourselves from HIV/AIDS we have other useful things. Our age level is full of problems. We are young people; we can be misled unless we get valid information. We get it [information] through clubs and transmit to others. We are now capable of disseminating to society. We also have good life experience while we discuss and work together"exemplary"we know how to behave, communicate, to be good role models for society. We are stronger through the Anti-Aids Club."

B. Enhanced personal knowledge and empowerment, with wider impact:

"Through the dialogue, club members have communication skills, experience in how to communicate with each other. We reflect their [young people's] potential. We connect information through dialogue and young people get current information. We pass ideas to community members, we pass them on to parents, families and classmates. Society members then get true information. Before there were misconceptions and even girls, they weren't allowed to join clubs."

C. Multiple gains through opportunities for girls and women to participate equally:

"My story is special as I lost both my parents to HIV/AIDS. There is a [young women's] association of young women and men who have lost their parents to HIV/AIDS. Unless I get awareness, even I may be infected by HIV/AIDS. This [AAC] makes me aware of how to prevent myself from AIDS."

"We girls are frightened to express our feelings. But when we are here we get motivation to express ourselves.

"In Ethiopian culture women are seen as inferior in society. Through this AAC we get empowered ourselves to speak! And we get support.

"I got invaluable information about HIV/AIDS and girls and about women's inequality. Unless women participate in every sector, there is no development. I can teach society what I got from this club."

D. Becoming positive role models with widening circles of impact; from participants, facilitators, families and villages and beyond:

"In our culture, reproductive health and menstruation is taboo. Girls cannot communicate with peers even [and] never with elders! Besides HIV/AIDS, we gain deep knowledge about this [through the dialogues]. The resonance is amazing " we can disseminate to families, schools, other villages, we can teach through experience and be role models."

E. Rich personal gains and empowerment through sustained active participation in which strong group identities and bonds are nurtured:

"We are a strong group with support and commitment, interest, motivation, strength in the group. We think more deeply about what we are doing, we have visions for the future. We think about questions from our work like becoming independent, how we can sustain ourselves, develop, build capacity, and how we work with other groups."

F. A sense of potential and more positive futures:

"Some AAC members have been promoted to government jobs and we can inform them through what we've got. Their informal education [from AAC] can help strengthen even formal education. We are students and this can help our formal education.

"In addition to prevention and control of HIV/AIDS we should research job opportunities by creating income generating activities. If we are ideal, people will say "be practical.' We need to create job opportunities."

These dialogues have also inspired the involvement of youth in diverse initiatives, with notable benefits for local communities.

II. Rural Community Conversation in Choko Village (some 20 km east of Awassa)

We travelled from Addis Ababa to Choko along a relatively good dirt road, passing garis"typical local transport of rickety two-wheel carts pulled by mangy horses and donkeys-along the way.

Garis in Awassa.

The conversation took place in Choko village, a lush, beautiful, densely populated area of small homesteads and gardens abundant with fruit, including avocados, sugar cane, bananas and khat cash crop, with orange flame trees stunning amidst the deep greenery.

The road to Choko village, Ethiopia, May 2006.

Widespread poverty and harmful traditional practices, lack of employment opportunities, lack of accessible services (including schools) and weak transport links are all major problems.

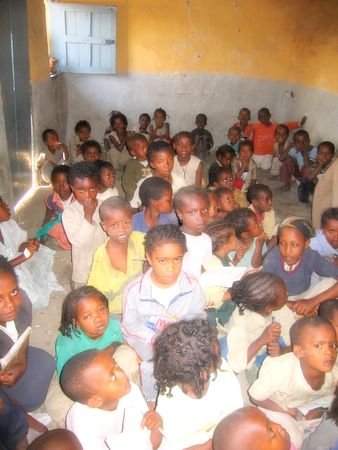

In this high-risk area " where workers in transit gather -- some 40 participants, ranging from teenagers to elders, squeezed onto benches in a garden outside the tiny local health centre, as they do fortnightly.

More than 40 community members gather for the conversation.

Photo by Afework Ayele.

As people sat in a wide circle under a tree, the atmosphere was lively and keen throughout, with much laughter and chatting and kids staring in at the gate.

Village children watched from the gate.

In the background were sounds of chickens, cows, birds, loud exhausts and squeaky wheels passing. Two UNICEF-trained youth co-facilitated, including a woman from the Department of Education. The focus was on why more local girls are not being educated. Discussion centred on the reasons behind this, reaching agreement at the end that the next session will explore how the community might better deal with the challenges discussed today.

Discussion focuses on why so few local girls receive any formal education.

Many women and men participated in the discussion that highlighted the following as negative impacts on girls' education:

"The main problem why girls don't go to school is abduction. [A widespread harmful traditional practice in this region is the abduction of young girls for marriage, particularly en route to schools which are long walking distances away]. It's been discussed and even the elders said stop abduction but it still exists."

"There is fear by families, especially in towns around, to send their daughters these distances. When they walk they could be abducted or get any other problem on their way to school and home. So they [parents] prefer to keep them at home and give them household activities."

"The economic problems of girls contribute to dropouts and there is no high school around here. After elementary school they have to go to Awassa [20 km, far away on typical local transport] and have to rent a house and food so they need more money. Without money they start other activities to fulfill their needs; either they get married or find other ways."

"Families and parents contribute to girls dropping out because of the perceptions and outlook. Families don't care for the education of girls, only for boys. Girls should stay at home. Even if they go to school, they have to work at home so have no time to study. Therefore they have low grades and are not promoted and will have to repeat and will quit. Families encourage them to sell tea and coffee and bring in money. The parents lack motivation and have a bad attitude."

"The dowry issue [is a problem]. Parents expect money from the men and think she [their daughter] will have a better life there. But it's not true; they'll show money to parents to take the daughter, but it's not true. So parents prefer getting the dowry to sending their daughters to school."

"Here people have over eight children typically. Even if they have money they prefer to buy school materials for boys. Girls? The parents rather they stay at home. Even to overcome economic problems families send girls into business, to sell. If the parents are doing business [small trade], girls must be at home to look after other children,[leaving no time to go to school]. So there is a real need for family planning."

"Girls drop out by themselves. Men give them money and they drop out. There are young men, this is a dynamic area with lots of movement, cash and sugar daddies."

Mothers reflect on their problems educating girls.

Reality was powerfully illustrated by a mother who shared her own story:

"Mine is an economic issue. I have two daughters, in sixth and eigth grade [eigth is the last grade of elementary school]. I need money for house rent and for food if they continue school in Awassa. So I'm thinking how can I send my daughter to Awassa? It is a major money issue for me."

A mother shares her problems educating two teenage daughters.

Interestingly participants also challenged some deeply-rooted hierarchies:

"Rules and regulations exist to punish those who perform abduction. But there is a tradition of sending the elders to negotiate [between the families to get the daughters released or the dowry paid]. The elders break the Kabale rule and they negotiate, so how will it work?"

This was inspiring to observe, both because of the process and active involvement of many participants of different ages, and because of the sensitive issues that came up spontaneously. The large turnout, keen interest, open discussion and questions were admirable. From the rapport and ease you would never have guessed that this was only the fourth meeting of this group.

Participants consider what the community can do to improve the situation.

Many harmful traditional practices are not easily discussed and certainly not among mixed groups of men and women of different ages. But in this atmosphere people were eager to speak and debate. This illustrates a major strength of community dialogue that fits particularly well with oral cultures, where face-to-face gatherings are customary and valued.

Following the dialogue the facilitators shared changes they have noticed and challenges they face. Even after only four sessions they already notice increased confidence, greater participation and asking of questions: "People are interested and ready to learn and discuss all issues."

Ailish Byrne and facilitators Bruknesh Aregaw, Jaleta Wata,

Shaleka Satto, Aster Dukamu and Buzunesh Kenafa.

Photo by Afework Ayele.

The facilitators shared their own initial fears that it might be difficult to gather people for discussion, but reality has proved "far more interesting and easier than expected." They are positive that the community will find ways of dealing better with their problems in future:

"It is a good experience working with the community and very hopeful. We are learning a lot from the community and from the process. We appreciate their openness, most come regularly, some come at 9 a.m. for an 11 a.m. start!"

They noted the issue of raised expectations that organisations like UNICEF ("donors") will provide more funding for community activities.

What Difference Does Dialogue Make?

These dialogues are typical of those occurring over much of Ethiopia today. They testify to the value of dialogue as locally grounded, something seen to come from within rather than outside, but aided and catalyzed by trained and supported facilitators. Encouragingly, on both occasions the groups spontaneously asked us why we were there, what we expected and what we brought. On one occasion the local facilitator was told off for attempting to answer on our behalf.

The dialogues clearly play an important role in the lives of individuals who regularly participate. They are not paid to participate and incentives, where they exist, are in the form of a coffee ceremony, soda and/or bread.

Many dialogues are in the relatively early days, but participants and facilitators are already raising key issues of sustainability, building wider alliances and achieving greater impact. Wider benefits include the empowerment of girls and women and free education being provided to local children with very limited opportunities, as witnessed.

We visited several initiatives involving youth dialogue facilitators that highlight the broader potential impacts of such experience.

Youth volunteer introduces the guests and poor children attending "school" to each other.

In three very basic sites around Awassa town, it was inspiring to see youth facilitators working as committed volunteer teachers to provide education to the neediest children living in circumstances of extreme poverty and lack of opportunity.

In an ex-police station, six volunteers teach girls in the poorest suburb of Awassa.

Thirty percent of the 100 or so children regularly attending the classes observed are HIV/AIDS orphans, typically from illiterate families. Although the children are hungry, they attend school regularly and HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Offices (HAPCO) is currently negotiating with the World Food Programme to provide meals. Many of these children would otherwise be on the streets.

The volunteers teach these children within very basic facilities.

Described as "an AAC in action," other dialogue facilitators were providing carpentry skills training and employment to fellow youth. With some material support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the government, the impressive carpentry workshop we saw has become largely self-sustaining. It now produces furniture on order for the government and other organisations, as explained by the dynamic young woman who manages the centre. Profit is split amongst the members.

Ailish Byrne and Tsegaye Petros, HAPCO, visit a successful carpentry

workshop run by local Anti-AIDS Association.

Afework Ayele talks with Medehin, the dynamic administrator of the

youth-run wood workshop.

We spoke with some 20 individuals personally involved in these initiatives. Their plans for the future, ideas and initiative, creativity, commitment and desire for opportunities to take the dialogues further was notable. Much is being achieved with few outside resources and minimal support.

In an "aid culture," in which the motivation and rationale of NGOs is often questioned, this is significant. People often say: "NGOs have their own interest, not based on our interest. Many NGOs follow donor interests, not community interests. This is a contradiction."

Those involved are well aware of the scale of the challenge:

"What is said and done should be compatible: There is a source, or root cause, of HIV/AIDS: It's poverty. If we can eliminate poverty [at least 85 percent of Ethiopians live in poverty], we can eliminate the root cause of HIV/AIDS."

Key ongoing challenges include securing basic resources, strengthening further the capacity of the people involved, capturing and sharing impact effectively, and ensuring progress and sustainability.

The Consortium has a strong partnership with UNICEF Ethiopia and other key groups. We will continue to consolidate and strengthen communication for social change processes by supporting wider and deeper capacity development, especially for documentation and participatory monitoring and evaluation, nurturing the building of wider alliances and supporting UNICEF and others to effectively engage with the media.

We want to help make sure that community voices and stories are heard at higher policy levels and that ultimately the impact of these CFSC processes will be enhanced.

Note: Special thanks to all facilitators and participants involved with the youth and community dialogues and to the young people who spent time sharing their experiences with us. Thanks to colleagues at UNICEF Ethiopia, in particular to Afework Ayele, who organized the field visits and whose interpretation was invaluable. Thanks also to Tsegaye Petros of HAPCO in Awassa.